“A producer of good quality livestock will always find a market for it” thats the motto adopted by Harry Gass a Cumbrian farmer who is optimistic about the future and firmly believes the Limousin will help his business stay in profit in the years ahead.

Harry Gass and his family run a 170-cow herd, as well as a large hill sheep flock, at Nunscleugh, near Brampton. Harry farms with his wife, Kitty, along with the couple’s son and daughter-in-law, Geoffrey and Jennifer and Harry’s brother, Alan.

The cows are predominantly Limousin, and the breed is also used to sire the high quality store youngstock which are sold at local sales annually. The farm, which lost 40 cows and two bulls during the foot-and-mouth crisis, has kept Limousins for the past 15 years, with a small proportion registered under the ‘Nunscleugh’ prefix.

The current policy is to move closer towards a virtually purebred Limousin herd, and Harry looks set to achieve his aim by around 2010. He is very clear about the reasons for his goal.

“Limousins carry flesh better, they have better conformation and they’re what the butcher is looking for. They are also easy to keep and very little trouble at calving – that is important nowadays, when everyone is under time pressure.

“You get two options with a Limousin heifer calf – you can either keep her as a replacement or finish her for beef. She will perform equally well either way, and there aren’t many breeds you can describe like that.”

When it comes to choosing stock bulls, Harry’s eye is drawn to an animal that is not too big, but has a well-shaped back end. His opinion is that these qualities should take precedence over liveweight gain records.

When it comes to choosing stock bulls, Harry’s eye is drawn to an animal that is not too big, but has a well-shaped back end. His opinion is that these qualities should take precedence over liveweight gain records.

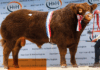

Harry believes he got a real bargain when he bid for Montgomery Uberto a 2003-born bull which came to the farm as a young calf with his dam. The pair cost just 2,000gns, and Uberto was initially tried out on a dozen cows with good results. This year the bull, by Mynach Pilot out of Montgomery Roberta, has served a further 50 females and his calves are looking promising. He originally came from RB Jones’ herd in Powys.

Another bull is Griseburn Vigilant, born in 2004 and bred by T. Horn of Appleby in Cumbria. Vigilant, is by Mynach Samson and out of Greenwell Fevorn.

Redrock Union has yet to have any calves on the ground, but the farm has high hopes of him, because of his good conformation. Union is by Sulki and out of a Shipptonlea female, and the family bid to 4,200 guineas to buy him at Carlisle sale.

Redrock Union has yet to have any calves on the ground, but the farm has high hopes of him, because of his good conformation. Union is by Sulki and out of a Shipptonlea female, and the family bid to 4,200 guineas to buy him at Carlisle sale.

AI has been tried on a limited number of cows, and it is only lack of time that prevents the practice being used more widely on the farm, says Harry. Despite using oestrus synchronisation frequently within the sheep flock, it has not been applied to the cows, although the idea has not been fully rejected and it may be something the farm will look at in years to come.

Running the farm leaves little time for showing, but the Gass family always enters an animal in the annual calf show and sale in nearby Longtown. They took the red ticket in 2005 and 2006 in the overall championship, and have won the award several times in the past (1996, 1997, 1999 and the Year 2000).

Harry, Geoffrey and Alan all work long hours on the farm, as well as employing a full-time member of staff. The 1,000 acre holding, with land rising to 600 feet and above, produces good grass. But, as Harry points out, “The land is strong and it’s not the driest place in the country.” Vitamin E and selenium are in short supply in the region’s soil, so all calves are given a booster injection to help them thrive. The cows also get supplementary copper.

One cut of silage is usually made by outside contractors during the last week in June. About 125 acres go into the clamp, with a further 75 acres made into big bales. Straw is a big expense, and one of the reasons why the business will continue to sell stores.

“On a farm like this, everything has to be bought in except grass, so we do not intend to finish any cattle in the future,” he says. “Neither do we have enough space in the buildings to carry any more animals, so it’s best that we carry on in the traditional way.”

The cows, which are split equally into autumn and spring-calving groups, come in during and October and go outside the first week in May. Nevertheless it has been known for cows at Nuncleugh to be brought in as early as September, to avoid poaching.

Most females are overwintered in cubicle housing, although there is space for around 50 head in a straw-bedded shed. The herd is fed on silage and minerals over the housing period, with calves also receiving a bought-in rearing nut.

The average herd age is six years, but some females have continued producing good quality calves until they reached 13-14 years old. Milkiness is a prime concern when selecting heifer replacements, but a compact shape is also important.

Spring-born calves are weaned in November and December, while autumn calves are taken from their dams by the end of July. They leave the farm at an average 12-14 months old, weighing around 400kg. Harry points out that Limousin-type stores are in good demand in the marketplace, often averaging £50/head more than other breeds.

Spring-born calves are weaned in November and December, while autumn calves are taken from their dams by the end of July. They leave the farm at an average 12-14 months old, weighing around 400kg. Harry points out that Limousin-type stores are in good demand in the marketplace, often averaging £50/head more than other breeds.

“Good store cattle production starts with breeding, and then it’s up to us to make sure the animals have an adequate diet in front of them. We like to sell between 90-100 cattle at the October sales in Longtown, then market the rest in January, February and March at Carlisle auction,” he explains.

“We have a buyer who takes 50 of our calves every year. Our aim is to produce calves in even batches, which makes for easier management and suits the butchers better. We like good tops and quarters, and cattle that are easy to feed.”

Harry’s family came to Nuncleugh in 1946, but after leaving school he was sent out to work on various local holdings. He recalls that when he started working as a farm labourer in 1957, his weekly earnings were just 4 pounds 10 shillings – and he was paid only once every six months. Having returned to the family farm when his father died in 1970, he started off with 40 cattle and 300 ewes, building up the business slowly.

Despite Harry’s conviction that beef production has a good future in this country, he stresses that it is important not to become complacent.

“It is no good sitting back and thinking you’ve arrived at your goal. You need to keep striving to improve all the time – I think that’s the only way forward,” he says.